Physics Rediscovered #9: Science is a giant pyramid scheme

Yes, you’ve read it correct and it’s no clickbait.

Science has been like that since forever. If you haven’t picked up on it by now, I will spell it out over the course of this episode.

But first, full disclosure: this article is not sponsored by the Catholic church, despite obvious and numerous product placements.

Now, with that out of the way, recall that in the previous episode we saw how Copernicus didn’t really rock the world with heliocentrism. I promised we would need to wait about 60 years for things to unfold.

It’s finally time.

From the church, with love

“Vehemently suspect of heresy“

and

“…foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture“

is what Galileo Galilei heard about himself and his ideas from the Roman Inquisition.

However, in it’s infinite wisdom and generosity, the church offered him a chance to recant under the threat of torture. Galileo, probably still smelling the burned corpse of another free-thinker of his time, Giordano Bruno, caved in and did what he was told.

Apparently, he didn’t do it convincingly enough, though. While the Church decided to skip on torture, they did insist on a lifetime-long house arrest.

But how did it come to this. How did things get so out of hand? Well, one could say it was inevitable.

Men who stare at chandeliers

To understand, we need to go back a few years, when Galileo was studying to be a physician, while really wanting to learn mathematics. It was family pressure, you see. Everyone wants a doctor in the family so they can brag about it, but a mathematician is just a schmuck, right?

Fulfilling his dreams, he managed to not become a doctor. That was a good decision as Galileo demonstrated a keen sense for physics early on. For example, when totally bored with a lecture on medicine he stared absently at the chandeliers swinging on the ceiling. He noticed that regardless whether the swing is small or large, it took the same amount of time. No stopwatches then, so he used his heartbeat to measure the time, instead.

Already you can see that Galileo was on a different level and he’s just 17 at the time. What the hell was I doing when I was 17? Something embarrassing, I’m sure.

Since then, things only got better for him. He went about his career, inventing several things (like the prototype of the modern thermometer), all of which gave him wide recognition, status, sponsorships and general swag.

At this point he’s also doing his leaning tower of Pisa experiment. You know, the one where he drops two balls of different weight and shows that they hit the ground at the same time? You know, the one you were led to believe actually happened? We only know about this from his biography, written by his student and most historians agree that the whole thing was just inside Galileo’s mind.

But that’s ok, it doesn’t matter. Similar experiments were being conducted in Europe at the time, all showing the same results. This was revolutionary in a way as it contradicted the dominating teaching of Aristotle, that heavier objects should fall faster. I swear, how did it take us almost 2000 years to question this nonsense.

Anyway, Galileo was on a roll and as it happens in life, things started to take a turn.

Padua noir

While in Padua, at the beginning of the XVII century Galileo developed a fascination with the night sky. Little did he know, this new passion would cost him. If this was a noir novel and Galileo was the jaded detective, astronomy would be the the femme fatale, that would rock his life.

It was late in the evening, even for me. The city around me was dead silent, exhausted after a whole day of bad choices, and foolish hopes. I was trying to get comfortable on my couch, which I knew I would fail. My hand was reaching for a drink. Not the first one today but I stopped counting a while ago. Then, a knock at the door stirred me from my lethargy. Despite the late hour, or maybe because of it, I took interest. A woman entered my office bringing with her a gust of cold, winter air. Her hair was pitch black with a single, wide grey strand, speckled with snowflakes that still haven’t melted. In the dim room her eyes seemed impossibly bright, cutting through the darkness. With a deep, silky voice, she said she needed my attention in a grave matter. Or maybe it was me who wanted her attention from the beginning. With little hesitation, I took the case…

… or something like that, you get the point.

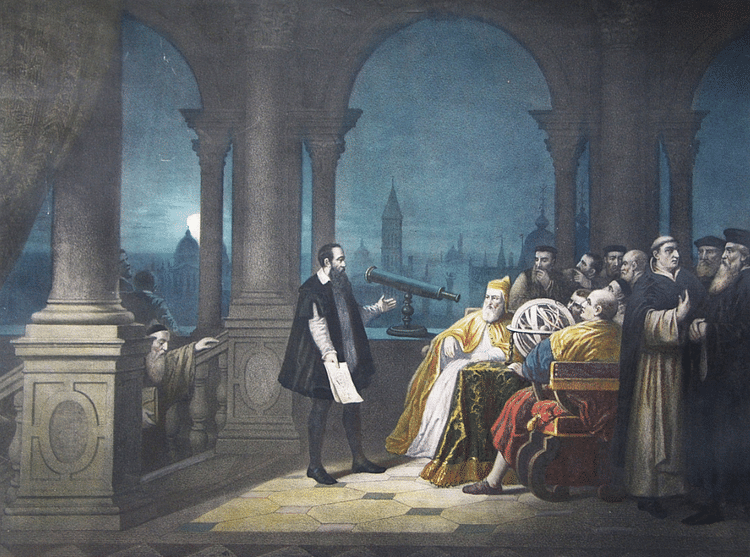

So Galileo knew that the night sky was pretty well observed at his time and if he wanted to make a difference, he would need a game changer. With that thought, he took a recent invention of the spyglass and adopted it into a refracting telescope to spy on the heavens.

He started with 8x magnification only to turn it up to 30x, later on. What he saw through the glass stunned him, the entire civilization and continues to do so to this day.

Imagine being the first human in history to see what he saw.

The Moon, believed to have a smooth glass-like surface, with occasional discolorations, now appeared rugged and hardly transparent. Galileo deduced that the shadows on the surface were due to mountains, valleys and craters, not unlike here, on Earth. Could be Moon be another world?

Then there was Jupiter and the three “fixed stars” that always seem to be next to it. What Galileo saw is that there are not three but four “stars“. Also, the fact that they sometimes disappear is not due to how dim they are, but because they hide behind Jupiter. That means, these are not stars, but moons, which we named: Ganymedes, Europa, Callisto and Io - the Galilean moons.

He described all his findings in what became a bestseller - the “Starry Messenger“. You can find it here. I recommend you give it a try as it’s pretty readable, despite its age. If not, then at least entertain this paragraph, summarizing his findings:

Some have believed that this structure of the universe should be rejected as impossible. But now we have not just one planet rotating about another while both run through a great orbit around the sun; our own eyes show us four stars which wander around Jupiter as does the moon around the earth, while all together trace out a grand revolution about the sun…

The heliocentric model just got even more credibility, coming out from hypothetical into factual. Perhaps even more importantly, the old Aristotelian thinking just got another nail hammered into its coffin.

No room for bullshit

Galileo had a real problem with the Aristotelian model of the Universe and not just because of its demonstrable inaccuracies. What really triggered him was the dogmatic and authoritarian way, in which it was accepted by his contemporaries. This is what he had to say on the matter:

And who can doubt that it will lead to the worst disorders when minds created free by God are compelled to submit slavishly to an outside will? When we are told to deny our senses and subject them to the whim of others? When people devoid of whatsoever competence are made judges over experts and are granted authority to treat them as they please? These are the novelties which are apt to bring about the ruin of commonwealths and the subversion of the state.

and

I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect intended us to forgo their use.

The dogma was so thick you could whack it over the head with a telescope. When Galileo wanted to conduct a live demonstration, many outright refused to look through the glass, certain that Aristotle already told all they needed to know. Perhaps they were really afraid of what they might see?

Galileo suffered no fools and took no prisoners. In his letter to Johannes Kepler, whom he greatly admired and who was also busy eviscerating Aristotelian thinking, Galileo wrote:

I wish, my dear Kepler, that we could have a good laugh together at the extraordinary stupidity of the mob. What do you think of the foremost philosophers of this University? In spite of my oft-repeated efforts and invitations, they have refused, with the obstinacy of a glutted adder, to look at the planets or Moon or my telescope.

This attitude and his passionate argumentation in favor of heliocentrism has started to get on the nerves of some powerful people. I don’t mean just the Catholic church here. Some hardcore Aristotelian philosophers, unable to counter Galileo on mathematical and physical grounds, reverted to religious argumentation to win the debate. Pretty desperate, right?

By now, everyone expects the inquisition

In 1615 Galileo is invited to Rome to defend his position on heliocentrism. A year later the Roman Inquisition deems it as contradictory to Holy Scripture, banning the works of Copernicus and Kepler. Because of course it does.

Pope Paul V requests that a cease and desist order be delivered to Galileo, saying:

…to abstain completely from teaching or defending this doctrine and opinion or from discussing it…

The delivery of this order is made by a certain cardinal Robert Bellarmine. This is the same fellow that, 16 years before, ordered to barbeque Giordano Bruno for having silly thoughts like: the stars being suns with planets of their own or the Universe having no center.

Having a sense that this is no Monty Python sketch, Galileo takes the order seriously, conforms and keeps his head down.

At least for now.

A few years go by and, wouldn’t you know it, Galileo’s friend becomes the new pope. Urban VIII, as we would know him, admires his friend and wasn’t a fan of how he was treated back in 1616. He tells Galileo that as long as he continues to discuss Copernicanism as hypothetical, rather than factual, then he’ll allow it, because that’s for friends are for.

Galileo sees this as a sign of good times and goes straight to work. In 1623 he publishes the Assayer (which we will return to shortly) and in1632 another bestseller - the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.

The Dialogue features three characters representing different worldviews: Copernican, impartial, and Aristotelian. The last one is named Simplicio. Galileo prefaces the book by saying that the name is derived from a famous Aristotelian philosopher, Simplicius. However, Simplicio is depicted in unfavorable light, to say the least. He is unable to counter arguments, often loses his temper and is a general dumbass. In Italian, the name also means simpleton. Not much room for interpretation here.

The pope reads it and would like his own arguments against Copernicanism to be included in a new edition. Galileo is more than happy to oblige and puts them in the mouth of Simplicio. Oooof!

In this outstanding move Galileo brings about another investigation upon himself. Now, we don’t know if that was all of the story, since Galileo is (in)directly involved in political quarrels through his patrons, the ever powerful and conflicted Medici family. However, it is the church that lands the final blow.

The trial for heresy is long and exhausting. The Inquisition finds that Galileo is not really going with the program, as he promised back in 1616. He tries to deny it but is betrayed by his own work. Because of his writings, there’s no doubt to what he really thinks about the whole thing. He is forced to make a “confession”:

…I am willing to remove from the minds of your Eminences, and of every Catholic Christian, this vehement suspicion rightly entertained towards me, therefore, with a sincere heart and unfeigned faith, I abjure, curse, and detest the said errors and heresies…

In the end Galileo is sentenced to house arrest for the rest of his life. Once again the Catholic church saves the day, defending us from scientists and free-thinkers. It’s going to take the church almost 400 FUCKING YEARS to admit that they maybe didn’t handle Galileo’s case very well.

The dawn of science

With his disdain for nonsense, dogma and authoritarianism, Galileo framed his work in such a profound way as to set the standards for centuries to come. In his writings, as verbally as no one before him, he laid out the foundations of the scientific method.

In the Starry Messenger he encourages other astronomers to scrutinize his work, like so:

But I shall gladly explain what occurs to me on this matter, offering it freely to the judgment and criticism of thoughtful men.

This is what we today understand as peer review, a fundamental checkpoint for publishing any scientific work.

In the aforementioned Assayer (which you can read here) he sets the norm, that there is no shame in changing one’s views when faced with facts, like so:

You take your stand on the authority of many poets against our experiments. I reply that if those poets could be present at our experiments they would change their views, and without disgrace they could say they had been writing hyperbolically-or even admit they had been wrong.

For Galileo, experimentation is fundamental to discovering the truth. He describes his entire scientific work in details, structuring in such a way to be reproducible be others. These sentiments are also present in the Assayer:

If experiments are performed thousands of times at all seasons and in every place without once producing the effects mentioned by your philosophers, poets, and historians, this will mean nothing and we must believe their words rather than our own eyes?

The reproducibility of experiments is an absolute must-have for establishing and validating scientific discoveries. Unfortunately, today’s economical incentives move us further away from this principle putting our pursuit of truth under serious threat.

Perhaps most importantly, no one has ever stated so verbally what was revolutionary back then, what we take for granted today, which will forever remain profound:

[The universe] cannot be read until we have learnt the language and become familiar with the characters in which it is written. It is written in mathematical language, and the letters are triangles, circles and other geometrical figures, without which means it is humanly impossible to comprehend a single word.

The scheme revealed

By now you must see the pattern that is emerging.

The ancient Greeks built on the mathematics of the Mesopotamians and the Egyptians.

Copernicus developed his model based on the philosophy and geometry of the Greeks.

Kepler made his discoveries inspired by the concepts and observations made by Copernicus and Brahe.

Galileo accomplished his work because of the contributions of Copernicus and Kepler.

Soon after another extraordinary mind would appear and, fueled by the works of Galileo and Descartes, would astonish the world with his brilliance. When asked how he did that, he would reply:

If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

There you have it. Giants standing upon giants, standing upon giants, in a never ending pyramid.

And with that in mind I will end this episode the way Galileo ended his Starry Messenger:

Time prevents my proceeding further, but the gentle reader may expect more soon.

First time here...great article, thx