We just explored how medieval engineers managed to hurl stones the size of body-positivity activists at people, causing them some mild inconvenience. All of that without knowing the classical mechanics that we do today.

Let's take a break from the Dark Age madness and do some basic physics for a change.

I wanna know how far that baby can throw.

We won't do any detailed mechanical calculations mainly because I just can't be bothered.

We'll actually do something more useful. We will consider the energies in the system. The vibes maaaan. Oh, and also some integrals... kind of.

Loose!

Read the energy

The trebuchet is a gravity weapon. The really heavy counterweight goes down, the throwing arm goes up. The rock flies. Simple.

In reality, some poor schmucks first need to get the counterweight up. However, as any good story would do, we will ignore these anonymous henchmen, who do all the work and focus on the main hero - potential energy.

Any mass changing position in a gravitational field in relation to the center of that field, gains or loses potential energy. Potential for what? To fall on somebody's head and make a terrible mess. As the counterweight gets lifted into position it gains some potential energy to waste later.

We can figure out how much that actually is. In order to do that we need to recreate the conditions similar to those when the trebuchets were actually fired.

We are going to start off by saying that we are on planet Earth. I thought this needed to be said. Back in medieval times the Earth's the gravitational pull, expressed as acceleration, was about 9.81 m/s². Nothing's really changed since then but I sounds more intriguing, right?

Based on some modern reconstructions, the counterweight itself was a big boy. Let's take one of about 6 tonnes. So how much potential energy can we get from this sonofabitch? This much:

ΔE = M g Δh

Here ΔE is the amount of energy we gain, M is the counterweight's mass, Δh is the change in height of the counterweight, once it is released (the actual height does not matter) and g is the gravitational acceleration.

Now, we could calculate what ΔE is, but that's totally unnecessary. We'll do something else instead. We will say that some of the potential energy gained is going to go into throwing that rock.

The energy of a rock soaring through the air, ready to bring about death and destruction is its kinetic energy. That being:

Eₖ = ½ m v²

Here, m is the mass of the rock and v is its speed at launch. Let's say we are throwing 100 kg boulders here.

How much of ΔE goes into the kinetic energy of the rock? Well, some goes into moving the throwing arm itself, some goes into friction and elasticity of the whole system. So let's say that 80% of potential energy goes into kinetic. If so, then:

0.8 ΔE = Eₖ

0.8 M g Δh = ½ m v²

I couldn't find how much the counterweight travels during the shot but Δh = 2 meters sounds reasonable to me. The only thing we don't know here is v so let's figure it out:

If we plug in all the numbers we get v = 43 m/s (156 km/h).

That's is faster than I expected.

Ok, we got the speed and speed is distance over time. To figure out the range or the distance the rock can travel before hitting the ground, we need to find the amount of time the rock stays in the air.

In order to do that, we will need an additional tool.

In general, we would like to jam like Newton and do calculus but that would be getting ahead of ourselves. Instead we will do integrals without doing integrals.

I promise this makes perfect sense.

Integrals foreplay

Consider for a moment what are you doing with your life and the concept of acceleration. Acceleration tells us how much speed we gain over time. Speed is expressed in m/s, time in seconds, so acceleration is m/s².

Let's say we'd like to figure out how much speed we will gain over some time when falling in Earth's gravity. Let's also make the offensive assumption that we aren't very smart. In that case we would go like this:

I gain 9.81 m/s for 1 second of the fall. I gain another 9.81 m/s for another second of the fall. That's 19.62 m/s for two seconds of the fall. Add another second of the fall, so another 9.81 m/s and we have 29.43 m/s.

If we call that 1 second interval "Δt" and remind ourselves that g = 9.81 m/s², then for those 3 seconds it's like:

g Δt + g Δt + g Δt

This feels kinda dumb. Let's take a different look and see if we can improve.

To the graph!

So we are looking at the acceleration (a) vs. time (t) plot. The value of our acceleration is g, throughout. Each of the colorful blocks represents g x Δt.

We can be stubborn and add those blocks for as long as we have some sort of acceleration. Also, instead of being cavemen, we can notice that adding those blocks amounts to calculating the area under the line, which is the area of a rectangle in this case.

This means that the speed gained over some time t is g x t. This is hardly surprising to anyone but a good logical frame for thinking about this. Can you feel yourself getting smarter? Can you?!

Let's get even smartererer. We've acquired speed from acceleration, now let's do it one more time to get distance from speed. It goes exactly the same way: some speed over a second gives me some distance, add over another second and another ... you know the drill.

But now we know that it's no different that calculating the area under the line. So let's do it, goddamit!

Now we are looking at speed (v) vs. time (t). From the previous plot we know that at any time v = g x t, which is represented by the white line. Now, if we just dropped whatever we are dropping then that would be it. End of story. However, we aren't just dropping things, we are launching them vigorously. That gives them some initial speed, which is represented by v₀. This simply means we are not starting at zero speed.

Calculating the area under v, or the white line, amounts to calculating the area of a trapezoid, but I decided to split it into two segments: a rectangle (blue) and triangle (grey).

The area of the rectangle is simply v₀ x t.

The triangle bit is simply half of a different rectangle. At any point in time the bottom side of this rectangle simply equal to t. The other side is equal to g x t, as we've seen a few paragraphs before, or did you already forget? The area of the rectangle is g x t², and half of that: ½ x g x t².

Putting both areas together:

½ g t² + v₀ t

TADA!!!

Now we know much distance we will be able to make over time with a constantly applied acceleration. With that, we can proceed to figure out the time of flight.

Seconds from disaster

Operating the trebuchet is a two dimensional affair. We have front-to-back (let's call it x) and up-down (let's call it y).

Let's say we are trebuchet beginners. This is our first time, we are a little nervous, we barely know what we are doing. We decide to setup the machine in such a way, that it launches rocks horizontally. In other words, when the boulder is released, its speed is parallel to the ground for a moment (it only has the x component).

At the moment of launch, the rock is released at some height (let's call it h). At what height? Let's see. There's the length of the throwing arm itself, which can be around a dozen of meters. Also, in those trebuchets the rock was not attached to the arm, but to a sling, which itself was attached to the arm. At full extension, the sling could also add a few meters. Let's say 20 meters in total.

Once released, gravitational acceleration immediately starts pulling the rock to the ground. So how does the vertical distance (y) behave? We now know:

give it the initial distance h

account for gravity reducing that distance (that's g with a minus in front)

ignore v₀, as we are launching horizontally, so no initial velocity in y

Overall:

y = h - ½ g t²

By definition, at the of impact or "Tᵢ", our y must be equal to 0 as that is the ground. So when the rock is eating dirt we have:

0 = h - ½ g Tᵢ²

and from that:

This is the time of flight.

This is as long as we are in the air tonight.

What is the range (or horizontal distance), available to the trebuchet, then?

We could say, that speed is distance over time, so that means that distance must be speed times the time. Time time time. That would be fine but now we have a framework so let's use it:

initial distance is 0, as we begin the measurement from the trebuchet

gravity works only in vertical so need to bother with that

initial velocity only is v₀, period

Therefore:

x = v₀ Tᵢ

What's the initial velocity? We actually calculated that in the beginning, when feeling out the energy. Scroll now.

Let's check out x:

Something crazy is happening here. Can you see it?

Let me write it a bit differently. I'm gonna pull out the g from both roots:

The g cancel out.

This means that the range of the trebuchet is independent of the planet we are using it on. Same on Earth, or Mars or the Moon, or the Sun or on a goddam asteroid.

THAT IS FUCKING INSANE!!!

How can this be? Surely this must be an error.

I mean, you launch the rock and gravity pulls it down immediately. Give it a strong enough gravity and the rock will drop in place right?

Well ... no.

Remember what I said in the beginning about the trebuchet being a gravity weapon? Well it truly is.

The gravity does the dropping, yes. However, it's also the gravity that does the launching, by moving the counterweight.

Give it a strong gravitational pull and the rock will drop fast but it also will launch with an oomph!

Give it weak gravity and the boulder will sail longer but it also will have less energy to begin with.

It all evens out. Pretty cool, huh?

OMG, what's the distance, already! Fine.

h is about 20 meters

the counterweight mass M about 6 tonnes

Δh - the distance travelled by the counterweight is about 2 meters

m - the mass of the stone is 100 kg

g - we don't care!

With that:

x = 87 meters

Pffff, that is shitty. We can do better.

No amateur hour

Let's do this again, but this time like we know what we are doing. This time we will setup the trebuchet such that we launch the boulder at a 45ᵒ angle. This is how we maximize the range but no time to prove it here. Trust me like you trust the government with your money.

We are no longer launching parallel to the ground so that means that our initial speed (v₀) will have an horizontal component (vₓ) and a vertical one (vᵧ). Our stone will now travel in an arc.

Going through the motions again, for y first:

initial distance h, same as last time

gravity pull down (again g with a minus)

this time we have vᵧ as our speed, pointing upwards

Together:

y = h - ½ g t² + vᵧ t

At the time of splatter (Tᵢ):

- ½ g Tᵢ² + vᵧ Tᵢ + h = 0

Dammit!

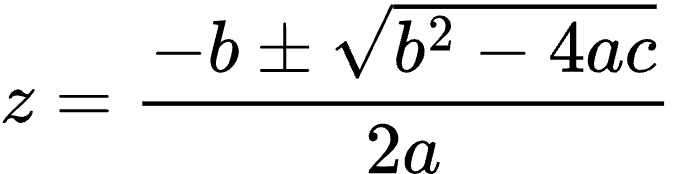

I hate it when it happens. It's a quadratic equation for Tᵢ. It's like:

a z² + b z + c = 0

What now? Well, fortunately the Greeks solved it for us way, way back as we've already seen here (scroll to the very bottom).

Ok, so if z is Tᵢ and a = - ½ g, b = vᵧ and c = h, and the general solution for z is:

Then:

From the possible choice of ± we have to take the minus sign (-) as this is the only possibility where the time comes out positive. Time machines weren't invented back in the middle ages, mind you.

For x nothing really changes much, except the horizontal component of the velocity, so:

x = vₓ Tᵢ

This means that:

Here, g does not cancel out so nicely. However, it still holds that g does not matter. It can be whatever. It won't make a difference.

From the pretty picture above we see that:

vₓ = v₀ cos(45ᵒ)

vᵧ = v₀ sin(45ᵒ)

After ramming in all of the numbers, we get

x = 210 meters

Damn that's tight!

We does this number make me happy? Because I didn't pull the parameters of the trebuchet out of my ass. I based them on Purton's "A History of the Early Medieval Siege c.450-1200", which are referenced here.

What's stated there is that a trebuchet with counterweight of 6 tonnes, hurling rocks of 100 kg can reach out to 200 meters.

So we are almost on point, which is somewhat miraculous given the assumptions we've made.

And with that we can all go to sleep content that we know the trebuchet's maximum range.

See ya!